17th Century

English Baptists in the 17th Century

There are two strands of thinking for the lineage of Baptists in the seventeenth century – one traces a line from continental Anabaptists of the sixteenth century and the other from separatist Puritanism under the Elizabethan and Stuart monarchs. What is certain is that a group of East Midlands Puritans emigrated to Amsterdam in 1607 and were there influenced by the Waterlanders, a Mennonite group. The English group’s views of salvation and church matured and they also underwent a baptism by affusion.

There are two strands of thinking for the lineage of Baptists in the seventeenth century – one traces a line from continental Anabaptists of the sixteenth century and the other from separatist Puritanism under the Elizabethan and Stuart monarchs. What is certain is that a group of East Midlands Puritans emigrated to Amsterdam in 1607 and were there influenced by the Waterlanders, a Mennonite group. The English group’s views of salvation and church matured and they also underwent a baptism by affusion.

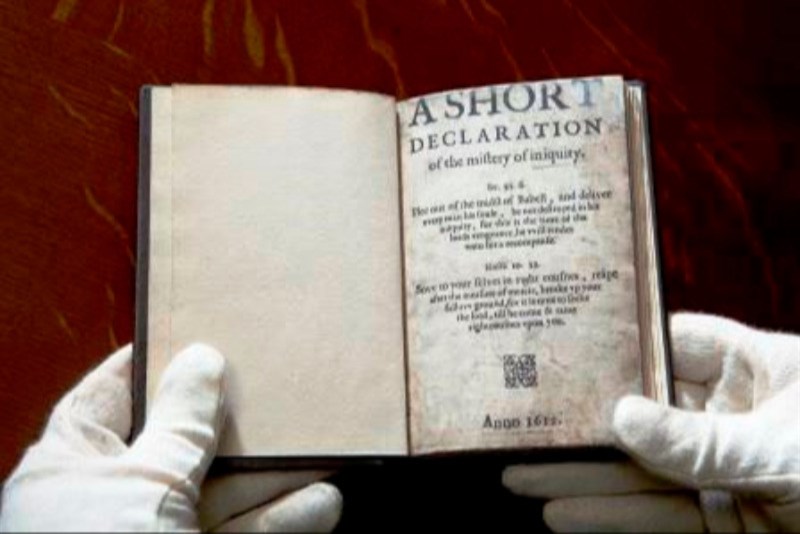

The group was led by John Smyth, a clergyman of the established church, and Thomas Helwys, a lawyer. Smyth subsequently joined the Waterlanders whilst Helwys and some of the church members returned to England and met together in Spitalfields. Helwys wrote an early plea for religious toleration The Mistery of Iniquitie, but was imprisoned and died in gaol by 1616. See articles here.

The group was led by John Smyth, a clergyman of the established church, and Thomas Helwys, a lawyer. Smyth subsequently joined the Waterlanders whilst Helwys and some of the church members returned to England and met together in Spitalfields. Helwys wrote an early plea for religious toleration The Mistery of Iniquitie, but was imprisoned and died in gaol by 1616. See articles here.

Calvinist Puritans established congregations, sometimes within parish structures and sometime separate. By 1638 some Separatist communities had adopted believers’ baptism as the mark of entry into the church and from the early 1640s immersion became the standard practice. So in the 1640s there were both Arminian (General)_ and Calvinist (Particular) congregations.

The outbreak of the Civil War had led to reduced censorship of the press and the state episcopal church was disrupted. In this context, the presence of Baptists grew, nurtured by publication of theological tracts and personal experiences. The establishment of local congregations was nurtured by the presence of Baptists in the Parliamentarian armies. However, geographical spread was still patchy

There were Baptists among the Levellers, who sought a radical settlement in the political life of the nation – too radical for Oliver Cromwell. In the 1650s Fifth Monarchist thought made inroads among some Baptists, although others rejected the idea that the return of King Jesus was imminent and his people should prepare the way by organizing godly living in personal and national life.

Despite a pledge of loyalty, the Restoration of Charles II drove Baptist activity underground, but although severely disrupted it was not extinguished. The Act of Uniformity had little impact on Baptist pastors but the Conventicle Acts bore down upon congregations and pastors, with meetings prohibited, attenders fined and pastors imprisoned. Prosecution of Baptists varied from area to area. The period of persecution ended with the accession of William and Mary in 1688, and the Act of Toleration of 1689 allowed freedom of worship and association. Baptists settled into a type of second class life, tolerated but still enduring civil disabilities, loyal to the monarchs and wary of the return of the Stuarts.

Although Baptist conviction asserted the autonomy of local churches, there was from the beginning interdependence too. From the 1650s, congregations formed self-chosen support networks called associations. Gatherings considered questions of theology, ecclesiology and political realities in the new era. During the Restoration, contact was maintained and in 1689 Calvinist and Arminian Baptists called a meeting for churches from across the nation.

In 1644 seven Calvinist Baptist churches in London had signed a Confession to set out their convictions and theological orthodoxy. Arminian Baptists in the East Midlands followed in 1651. In 1689 the Second London Confession was adopted by the Calvinists at the first gathering in London of the post-Stuart era, having been first produced in 1677. It would become the standard statement for many years (and for some places in the world still is). The Arminian General Baptists too produced a Standard Confession in 1678. See articles here.

The new Baptist world generated questions and queries, for example was it right to pay tithes? Could a Baptist marry outside of the church fellowship? Doctrinal issues emerged too: the Calvinist dispute in the 1690s over the singing of hymns; and for the Arminians, the differences over Trinitarian theology and the rite of laying on of hands on the newly baptized.

Women often outnumbered men in the congregations and were received as members but the radical edge of some early Baptist women was blunted as the churches settled into traditional gender roles. See articles here. Leadership was restricted to men.

From the 1640s, some early Baptist leaders had been clergy in the state church but most were people who had been convinced of Baptist views. Baptists numbered significant thinkers and activists including William Kiffin, Thomas Lambe, Hanserd Knollys, John Tombes, Thomas Grantham, Thomas Collier and most famously John Bunyan. As the ‘heroes’ of the past decades grew older and died, the challenge came for a new generation of leaders.

Pastors were chosen by agreement of the membership. Meetings of the members considered finance, applications for membership and issues of pastoral discipline. Neither Calvinists or Arminians created training establishments for ministers, although a few Baptists would take advantage of academies run by Independents. Most though developed their own thinking through reading, reflection and conversation.

The Seventeenth century was a time for emergence and growth amongst Baptists, although still only a small part of the population. The Restoration undoubtedly checked advances but the new century beckoned, Baptists could look forward with a measure of cautious optimism to life under a more accepting political regime with greater freedom in religion.

Related Articles